The EU AI Act was finally signed into law on March 13 by the European Parliament, with 523 votes in favor. While there’s much commotion about it in the media, comparatively few truly grasp its contents, which isn’t all that surprising: the final draft of the Act is a rather tedious 300-page read. With that in mind, we decided to provide our readers with a concise overview, making it easier to understand what to expect in the Euro AI landscape in the upcoming months and years.

What is the EU AI Act?

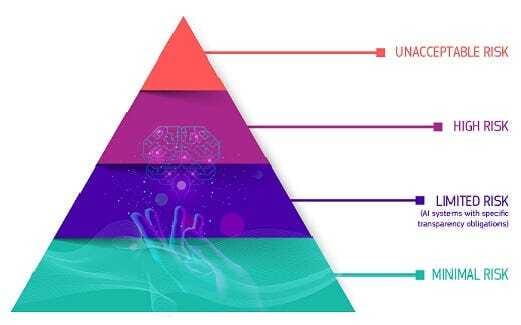

In a nutshell, the EU Act is a comprehensive legal framework that categorizes AI systems based on their risk level, ranging from unacceptable to minimal. It aims to ensure that AI systems are safe, transparent, and accountable for use within the EU.

Definitions and jurisdictions

AI developers are referred to as “providers” (e.g., OpenAI). They can be either “upstream,” (i.e., original model creators) or “downstream” (i.e., those integrating another company’s model into their AI solution). Downstream providers can sometimes also be deployers.

Deployers are referred to as “users” (e.g., a bank using ChatGPT to process loan applications). A sharp distinction is, therefore, made in the Act between “users,” who are essentially corporate or state entities, and “end-users,” who are essentially private individuals.

The geographic location of AI parties does not exempt them from compliance with the EU AI Act, with the new law applying universally within the bloc. This means that both developers and deployers from abroad are held accountable for their AI technologies, so long as they impact EU member states.

Developers/providers are deemed most accountable, with deployers/users bearing responsibility to a lesser extent. In other words, if an unscrupulous AI product enters the EU market, it’s the developers of this solution who’ll have to answer, first and foremost.

Different risk levels

Source of the image: the EU Commission

The Act’s framework identifies four risk levels: unacceptable risk, high risk, limited risk, and minimal risk.

An unacceptable-risk AI system (e.g., untargeted scraping) implies that its potential threats cannot be mitigated. These AI systems are explicitly defined and prohibited.

Most of the Act is dedicated to high-risk AI systems (e.g., filtering of job applications): the most “troublesome” AI systems that are valuable enough to stay but hazardous enough to require transparency.

Limited-risk AI systems (e.g., company chatbots) fall under more lenient regulations. The main requirement is for the deployers of these systems to inform the end-user about their interaction with AI.

Minimal risk AI systems (e.g., spam filters) are left unregulated in the Act.

Prohibited AI systems

Unacceptable and hence prohibited AI systems are basically those that utilize discriminatory practices, leading to psychological, financial, or physical harm, as well as those causing privacy violations, manipulation, and breaches of fundamental rights.

These include social scoring (i.e., rating individuals according to “sensitive” traits like sexuality), web or CCTV scraping (i.e., automatically collecting images for databases), deploying real-time remote biometric identification (RBI) systems (i.e., identifying individuals from a distance without consent), or using emotion recognition solutions (except for medical reasons).

EU law enforcement agencies are permitted to use certain banned biometrics and RBI systems in the course of duty. Exemptions also extend to third parties involved in special cases, such as searching for missing or abducted persons, preventing imminent threats, and fighting crime.

Deploying these otherwise illegal AI systems requires registration in the EU database and authorization from a judicial or administrative body. Notably, these procedures can sometimes be temporarily bypassed, with post-factum authorization required within 24 hours.

High-risk AI systems

According to the Act, high-risk AI systems are identified as those that profile individuals based on important but “less sensitive” characteristics (e.g., location and movement patterns), as well as those that involve non-banned biometrics (e.g., securing access to devices or premises), those that touch HR (e.g., candidate ranking or termination of contracts), and those that concern essential services (e.g., benefits eligibility or insurance appraisal) among others.

All upstream, as well as downstream, developers and sometimes also third-party deployers of high-risk AI products must establish mandatory risk management, quality control, and data governance mechanisms within their systems. This is necessary to ensure accuracy, transparency, and cybersecurity, including automatic recording in escalated scenarios, as well as human oversight.

General purpose AI (GPAI)

General purpose AI (GPAI) systems are designed for a broad range of applications — from direct use to integration into other AI systems, including those posing high risk. GPAI models used for research, development, and prototyping prior to market release are not covered in the Act.

There are four major requirements all GPAI model developers must comply with:

Create and store technical documentation detailing the training, testing, and evaluation processes of the AI model.

Publish categorical summaries of all data from every ML training phase.

Provide paperwork to downstream providers outlining the model’s capabilities and limitations.

Establish and uphold copyright directives.

Note that for open-source GPAI models, only copyright adherence and training data summary publication are compulsory — unless these models are deemed systemically risky. A systemic risk is defined in the Act by the significant computational power used in training, which is set at over 10^25 floating point operations per second (FLOPS). The basic logic here is that models trained this way raise concerns due to their potential for amplifying biases.

Developers of such models must notify the EU Commission within two weeks if their models meet this threshold. Models identified as having systemic risk must undergo further evaluations, including adversarial testing (i.e., determining how the system behaves when faced with malicious input).

Execution and timelines

The AI Office is tasked with overseeing the execution of the Act. Downstream providers and deployers have the right to file complaints against upstream providers for any regulatory breaches.

The timeline for the Act’s implementation is as follows:

Unacceptable-risk AI systems will be identified and banned within six months.

GPAI models will be subject to regulation within one year.

High-risk AI systems will be regulated within two to three years, depending on their classification.

The Act’s shortcomings

We at AIport can reasonably foresee some challenges in the Act’s enforcement. These may arise at some point for two major reasons.

The first one relates to the use of prohibited AI solutions in exceptional situations. This privilege can be invoked after presenting “objective, verifiable facts” to relevant authorities; however, the objectivity of these facts can often be difficult to gauge, as they are subject to interpretation. Sometimes, authorization can be altogether suspended, which sounds a bit like “it’s banned… unless we really need it.”

This represents one of the Act’s loopholes that could potentially lead to misuse, with unregulated GPAI models used for research and development opening another possible avenue for exploitation.

The second issue, the Act’s Achilles heel, is about the versatile nature of AI technologies and conceivable ambiguities in an AI system’s intended use versus its actual application.

Consider this analogy: manufacturers of frying pans design their products for cooking, yet they cannot prevent someone from utilizing these pans as impact weapons (i.e., taking a pan and hitting someone over the head with it). Likewise, AI solutions, though designed with specific uses in mind, may be repurposed contrary to their intended function. Other times, developers of GPAI technologies, like Gemini or Claude, cannot fully predict or control every application of their product in spite of their warnings to deployers and end-users.

While the Act is meticulous in its approach and does a decent job of differentiating between distinct types of AI tools, the second issue in particular remains its main blind spot, largely by default. This means that a blame game between developers and deployers, as well as upstream and downstream providers, could ensue in tricky situations, with finger pointing in both directions.